To view the complete PDF of this story, click here.

By Renee Changnon, rchangnon@nrha.org, Kate Klein, kklein@nrha.org, Melanie Moul, mmoul@nrha.org and Todd Taber, ttaber@nrha.org

Menards is a big-box enigma in the U.S. home improvement industry.

Older than Home Depot and smaller than both Home Depot and Lowe’s, the Wisconsin company has stayed quietly regional and privately owned for more than 50 years and counting.

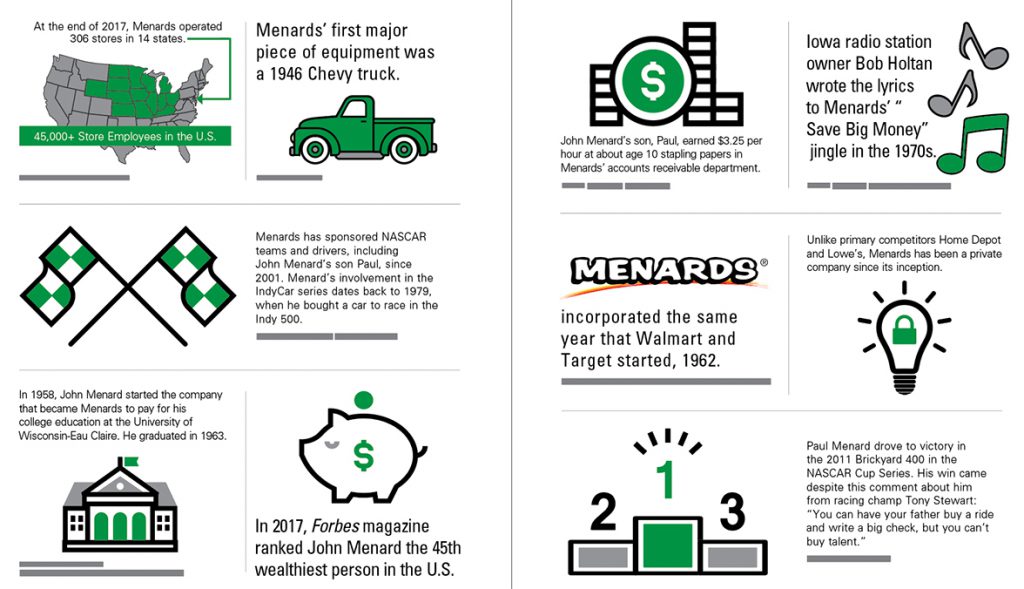

At the same time, the bold lettering on Menards-sponsored race cars, the iconic “Save Big Money” jingle, and the founder’s reputation are not quiet. Founder John Menard cannot avoid public scrutiny, as he lands on Forbes’ annual list of American billionaires year after year and appears at NASCAR races to watch his race car driver son, Paul.

But, as a private company, the third-largest home improvement retailer in the U.S. does not release financial information, unlike its publicly traded competitors and independent cooperatives such as Ace Hardware and True Value.

In addition, Menards’ leadership has mostly avoided requests for media interviews and closely controls information the company releases. Hardware Retailing has been among the media outlets that have contacted the company for more information without receiving a response.

A comprehensive look at how Menards operates is difficult to get, and people who haven’t worked in executive roles within the company know little about it.

Because few public documents are available and Menards did not provide interviews, Hardware Retailing writers compiled information from existing research and approached retail industry observers for added insight.

Read on to find the results of their work in a 360-degree look at the company.

The History of Menards

The year 1962 was a busy one in American retail. That year, entrepreneur Sam Walton opened the first Walmart store in Rogers, Arkansas;1 in Minneapolis, the first Target retail store opened;2 and John Menard incorporated Menards as a Wisconsin company.3

Walmart would grow its discount model astronomically and permanently transform

the way businesses buy, sell and transport products worldwide. Target became a national company known for its trendy products and strategic business partnerships with fashion designers and companies such as Starbucks. Both general merchandise retailers went on to become public companies with stockholders around the world.

Throughout the nearly 50-year boom of discount retailers and home improvement competitors, Menard kept his business closer to the vest. He maintained controlling ownership, and as a result, kept the independence of growing and experimenting with retail concepts in relative privacy.

Throughout the nearly 50-year boom of discount retailers and home improvement competitors, Menard kept his business closer to the vest. He maintained controlling ownership, and as a result, kept the independence of growing and experimenting with retail concepts in relative privacy.

In the home improvement sector, Lowe’s Cos. had been steadily growing in the Southeast for nearly two decades when Menards incorporated. Lowe’s opened for business in 1946 and, just one year prior to Menards’ incorporation, went public in 1961.5 Home Depot entered the home improvement marketplace with two stores in 1979 and went public in 1981.6

Menards was born out of a growing local demand for pole buildings. Menard began his business to serve the rapidly changing farm industry in 1958.7 As more machinery was introduced into dairy farming, he recognized a need for low-cost agricultural buildings to house livestock and equipment.7 Within a year, Menard’s pole building construction business was already gaining a reputation in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, where Menards’ corporate headquarters is now located.7

As consumers started requesting lumber and building materials, Menard entered into the building materials business, calling his retail outlet Menard Cashway Lumber and opening the first retail location in 1964.4

The company expanded into manufacturing more substantial building materials on-site, opening a truss plant in the late 1960s.7 The truss plant eventually developed into the Menard Building Division and manufactured steel siding and roofing, interior and exterior doors, decking and treated lumber and other materials.7 Menards sold the Menard Building Division in 1994, ending more than 30 years in the pole building business.7

During that same period, the company operated 78 Menards stores.4

An early experimentation for the retailer was using an efficient delivery system to supply its stores. Menards was the first DIY home improvement company to use the “hub-and-spoke” system, with all deliveries originating from the company’s distribution facility in Eau Claire.4

Home Depot and Lowe’s would later adopt similar distribution strategies, and a Forbes analyst speculates that the companies were inspired by Menards to implement similar methods in their businesses.

Menards supplied all of its stores from its distribution center in Eau Claire until 1998, when a second center opened in Plano, Illinois, according to the company. Menards now operates 11 distribution centers in eight states, including two in Wisconsin and three in Iowa.7

1 corporate.walmart.com

2 corporate.target.com

3 Office of the Wisconsin Secretary of State

4 Forbes (multiple articles)

5 Lowes.com

6 corporate.homedepot.com

7 Menards.com

Timeline: From 1958 to the Present

1958: In the Beginning—John Menard starts a business constructing pole buildings in

his hometown of Eau Claire, Wisconsin.

1962: Big-Box Boom—Menard incorporates3 the company in Eau Claire the same year Walmart1 and Target2 open their first retail stores.

1963: Business Acumen—Menard graduates from the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire

with a degree in business administration.8

1964: Retail Outlet—The first Menards retail location, called Menard Cashway Lumber at the time, opens in Eau Claire.

1969: New Ventures—Menards launches its truss plant, which became Menards Building Division and manufactured building materials, such as siding.

1990s: Growth and Change—Menards doubles its store count throughout this period. The company sells Menards Building Division in 1994.

2000s: The Big Time—Menards opens several large-format stores, each at more than 200,000 square feet, throughout the Midwest.10

2016: Labor Trouble—The National Labor Review Board rules Menards violated federal law, its second violation in as many years.9

The source for the timeline entries is Menards.com, unless noted otherwise.

8 University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Alumni Association

9 Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

10 Time magazine, March 19, 2013

Who Is John Menard?

The story of Menards is incomplete without a short biography of founder John Menard, who not only built the company, but has also directed its course for decades.

Born in 1940, Menard was the oldest of eight children and “learned the value of hard work and frugality” while doing chores on his parents’ dairy farm in Wisconsin, Mary Van de Kamp Nohl writes in Milwaukee Magazine.

In the 1950s, Menard was a young man working to pay for college in Eau Claire who saw an opportunity for entrepreneurship.7

Menard set out to start his own business when he left his high school job to construct pole buildings. His customers asked to buy building materials, so he went into retail, opening the precursor to today’s Menards stores, Menard Cashway Lumber.11

In business, Menard is detail-oriented, thrifty and an opportunist, similar to many retail entrepreneurs who built large companies in the 20th century.11 Like Sam Walton, who founded Walmart, Menard has been carefully frugal, opting for a lowest-price-possible retail model and negotiating heavily with vendors to slash product costs.11

Also like Walton, he is willing to try selling a broad array of products in his stores, including groceries, diapers and toys, alongside traditional home improvement departments such as electrical supplies and lumber and building materials.

Menard stands out as eclectic, with a penny-pinching approach to business but a famous, expensive interest in car racing.11 In addition, he has provided material for tabloid-style writing due to friendships and fallings out with other billionaires, including President Donald Trump.12

In a 2013 article, Forbes reports that Menard told the magazine he no longer runs his retail chain. However, “insiders say he still oversees the smallest details, from the material for store parking lots to answering company mail,” Forbes says.

Perhaps confirming active involvement in the company, Menard made a public appearance with car dealer Tom Kelley in March to announce a business partnership that would include expanding two Menards stores in Indiana.13

Regardless of how active he is in the company currently, Menard, at nearly 80 years old, is the wealthiest Wisconsin resident and one of the richest people in the U.S.4

11 Milwaukee Magazine, April 30, 2007

12 Indianapolis Monthly, Indianapolis Business Journal

13 The Journal Gazette, March 7, 2018, Fort Wayne, Indiana

A Snapshot of Menards

Menards in Recent Years

Menards currently has more than 300 stores in 14 states: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, Wisconsin and Wyoming.7

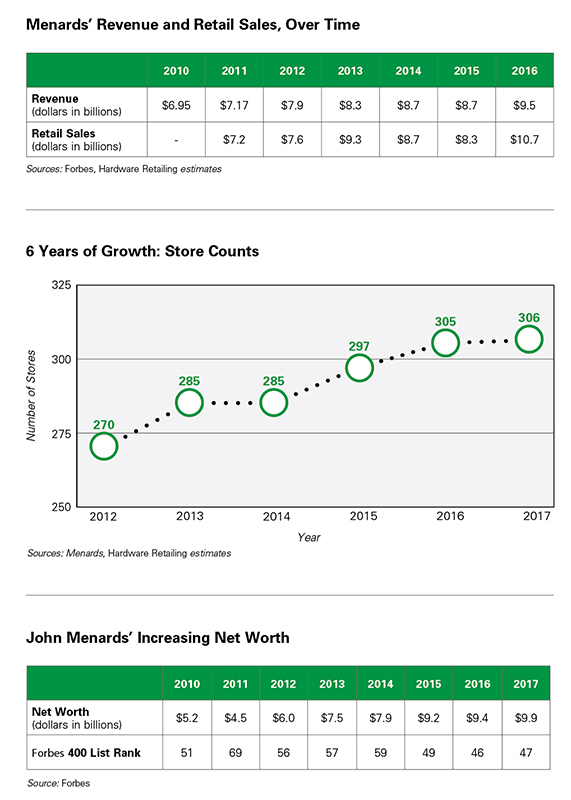

The company employs an estimated 45,000 workers,7 and the National Retail Federation estimates the company pulled in $10.7 billion in sales during fiscal year 2016. That estimate is about $84 billion less in 2016 sales than Home Depot reported and about $54 billion less than Lowe’s.

However, according to Hardware Retailing estimates, Menards’ sales ring up at about

$6.4 million less per store than Home Depot, and $4.6 million more per store than Lowe’s.

Big-box retailers like Target, Walmart and Lowe’s have been rolling out small-format versions of their stores. However, Menards has expanded into more locations throughout the Midwest with buildings that are larger in size than their predecessors and retail competitors, too.

In 2011, Menards debuted its remodeled Eden Prairie, Minnesota, store, which was a 235,000-square-foot, two-story operation, according to a 2012 article in the Minneapolis Star Tribune newspaper.

“Menards has accomplished contradictory feats: It builds stores of enormous size at a time when retailers are downsizing, while also maintaining its reputation as a salt-of-the-earth, family-owned business,” the Star Tribune reports. “The retailer has somehow merged intimacy and big box into the same sentence, retail observers say.”

While some companies wouldn’t want to close up shop to remodel a massive building, Menards has done that in many situations. The company can likely do so because of its private ownership.14 Menards has the flexibility to make changes without reporting to a massive number of stockholders.

While some companies wouldn’t want to close up shop to remodel a massive building, Menards has done that in many situations. The company can likely do so because of its private ownership.14 Menards has the flexibility to make changes without reporting to a massive number of stockholders.

In addition to expanding salesfloors in many of its existing stores and new locations, Menards has also made a name for itself with its eclectic mix of merchandise. Customers can expect to find everything from standard hardware tools and gardening equipment to groceries and furniture.

The company has gained a reputation similar to Walmart, reassuring its customers they can “Save big money at Menards,” as their iconic jingle says.

The company reports that its stores offer the lowest prices in town and a wide range of categories housed under one roof, creating a one-stop shop for customers.7

Dropping Prices and Internal Manufacturing

Menards has built a reputation as the destination for low-priced home improvement goods. The company’s rebate program draws customers back to stores, as its policy of giving in-store credit instead of cash pays off.14 This approach inspires customer loyalty, as they return to use their credit in the store and spend more money in the process.

Menards demands low prices from its suppliers to keep its low-price promise to its customers. On top of working with brands to get deals on merchandise, the company also keeps prices low by manufacturing many of its building materials, which include doors, roofing and siding.

In July, the company was finalizing plans to open a new manufacturing operation in Holiday City, Ohio. Menards will be manufacturing a variety of materials, such as steel roofing and siding, and concrete blocks. Plus, the facility will act as another distribution center for Menards.15

In December, the Leader-Telegram in Eau Claire reported on the company’s plans for a new warehouse run by machines.

Menards “plans to build a 121,700-square-foot warehouse with a 60-foot-tall automated system that will organize merchandise and process orders,” the Leader-Telegram reports.

The goal for this addition is to get products to customers faster, Jeff Abbott, spokesman for Menards, says in a statement.16

“The robotic warehouse allows the company not only to speed delivery time but also cut costs and keep prices low,” Abbott says in the newspaper article.

In addition to manufacturing projects and distribution enhancements, Menards continues to open stores throughout its current service area. In March, John Menard joined Tom Kelley, president of Kelley Automotive Group, in Fort Wayne, Indiana, to announce expansion plans for Kelley’s business and Menards.

The company plans to invest up to $6 million to expand its stores to upgrade the size, product line and service in two Fort Wayne Menards locations. Kelley plans to invest millions in updates to nearby land.13

Fines, Lawsuits and Disgruntled Employees

While founder John Menard has created a company from the ground up, and in turn has become the wealthiest person in the state of Wisconsin, his rise to success has come with scrutiny for him and his business.

The company has faced different legal challenges over the years, and currently is dealing with lawsuits from former employees. For example, in 2015, managers at the company shared that in their employment agreement, they had to agree to a substantial cut in pay should the workers under their supervision form a union.17

Lawsuits followed, and by April 2016, the National Labor Relations Board found Menards guilty of violating multiple federal labor laws.18 The violations could impact the company’s relationship with all of its employees, the article says.

In February, an Ohio law firm sued Menards “on behalf of workers who say they weren’t properly paid wages and overtime,” the Dayton Daily News reports.

14 Star Tribune, Jan. 29, 2012, Minneapolis

15 The Blade, July 12, 2017, Toledo, Ohio

16 Leader-Telegram, Dec. 1, 2017, Eau Claire, Wisconsin

17 The Progressive, Dec. 15, 2015

18 The Capital Times, April 1, 2016, Madison, Wisconsin

SWOT Analysis

Strengths

- Broad Inventory. From plumbing and electrical supplies to sports drinks and plush dinosaur toys, Menards is known for its wide selection. In 2017, customer experience analysis firm Market Force Information surveyed 7,800 U.S. consumers to learn about shoppers’ opinions of home improvement stores. Menards scored highest in the merchandise variety and value category, topping Ace Hardware, Home Depot and Lowe’s.

- Memorable Marketing. Menards’ signature “Save Big Money” song is memorable and has run on TV and radio for decades. The retailer’s billboard and print circular advertising often looks like it could have come from a local business, and some of the language sounds similar to small business marketing material, such as,

“Put your money where your house is.” Menards has also advertised on race cars, emblazoning its logo on Menards-sponsored vehicles and race team uniforms. - An Affordable Reputation. Menards’ “Save Big Money” mantra and regularly advertised 11 percent discounts on products have helped the company establish itself as an affordable option against competitors, according to Anne Brouwer, retail consultant from the firm McMillan Doolittle.

- Business Diversity. In addition to its retail outlets, Menards operates subsidiary businesses, including Midwest Manufacturing, Menards Self Storage, Menards Transportation and Menards Real Estate.

Weaknesses

- Mobile App Adoption. Menards, as a regional company, is a distant No. 3 behind national companies Home Depot and Lowe’s in many areas. For example, Market Force surveyed more than 7,800 Americans and learned that their usage of Menards’ mobile app lags behind use of apps from Lowe’s and Home Depot. The Menards app offers bar code scanning to learn more about products, in-store department maps and augmented reality to help customers visualize home renovation projects.

- Store-Branded Credit Card Use. Menards also trails its main competitors, Home Depot and Lowe’s, in the number of consumers using its store-branded credit card, the Market Force survey reveals. Among respondents, 25 percent used Lowe’s credit card, 21 percent used Home Depot’s and 7 percent use Menards’ store-branded credit card.

- Being Regional. Brouwer calls Menards

“a regional player.” Because the retailer operates stores in only 14 U.S. states, many Americans do not have local access to Menards locations but can shop at the brick-and-mortar locations of the company’s largest big-box competitors all across the country. - Unclear Trajectory. If founder John Menard is still the business’ majority shareholder and continues to provide close operational oversight, then the company’s future is highly dependent on an untested succession plan.

Opportunities

- Repurposing Vacant Stores. In January, U-Haul acquired a vacant Menards store in Indianapolis. U-Haul plans to renovate the building and use it as a self-storage facility, according to uhaul.com. Menards could continue to sell vacant stores to noncompetitors to earn money if stores close.

- Capitalizing on E-Commerce. Menards has the financial means to bolster its e-commerce offering in a way smaller retailers cannot. By investing more in e-commerce, the retailer could increasingly reach customers in locations where it does not physically operate brick-and-mortar locations.

- Investing in Technology. In 2017, Menards announced plans to build a new distribution center featuring a robotic system to speed up delivery times and cut operating costs. If effective, Menards could replicate its success by renovating existing distribution centers or building new facilities.

- Increasing Productivity per Store. Brouwer reports that while all Home Depot, Lowe’s and Menards locations are roughly the same size, Menards’ stores often earn less per store. By increasing productivity and sales at existing locations, Menards could close the gap.

- Adding Distribution Centers. Menards currently has at least 11 distribution centers. The retailer could add facilities where it does not currently have a brick-and-mortar presence to facilitate deliveries and better serve markets outside the company’s Midwest base.

Threats

- Distant Third. In 2017, The Home Depot scored $100 billion in fiscal year sales and Lowe’s earned $67 billion. The National Retail Federation estimated Menards saw $10.7 billion in sales in 2016. Menards is in a distant third place among the nation’s top three big-box home improvement centers, though it is 16 years older than Home Depot.

- Legal Entanglements. Both Menards the company and its president and CEO John Menard have faced several lawsuits over the years covering a wide range of issues, including environmental violations, wage theft and sexual harassment. These legal issues could potentially be costly both financially and in terms of the retailer’s public image among employees and customers.

- Closing Loopholes. Menards has been able to reduce its taxes by arguing that its stores should be taxed as if they are empty, not as operational businesses with full, diverse inventories. Tax loopholes in several states have allowed Menards and other retailers to diminish their tax burdens, but as states tighten regulations, Menards’ costs will

also increase. - The Independent Sector. Independent operators, including businesses with Ace Hardware, Do it Best and True Value branding, run successful stores near many Menards locations, and often have reputations for better service and higher quality products.

Unless other sources are cited, the opinions expressed in this SWOT analysis are based on market knowledge and research from the Hardware Retailing editorial team.

The Financials

Menards on Its Home Turf

Hardware Retailing (HR): How would you describe the economic role Menards plays in Wisconsin?

Thomas Kemp (TK): Menards is the dominant home improvement chain, certainly, here in Eau Claire. They’re also the single largest employer in the city employing around 3,000 people, so of course they have a huge economic impact on our local economy because of that.

HR: Menards is one of the largest private companies in the U.S. How does that benefit Wisconsin?

TK: I think it benefits the state because the control is local. Because Menards is based here in Wisconsin, their interests are—to some extent—in line with the needs of the state, so I think that’s helpful locally. Their roots from the very beginning are closely tied to Wisconsin.

HR: In your opinion, what are Menards’ greatest strengths as a company?

TK: I think their greatest strength is being flexible in terms of their business plans. I’ve grown up with Menards my whole life, and they always seem to be in tune with what a community needs. If they notice that another retailer is doing something that they think they can do better, they go ahead and do that, even if it’s not totally central to their core mission of home improvement.

For example, they generally carry a line of foodstuffs and that’s consistent with their broader business plan of offering relatively high-quality products at low prices. They’re very creative with product lines.

HR: What are Menards most effective growth strategies?

TK: It seems to me that Menards is remarkably in tune with their particular value prospect. That’s likely the key to their success in terms of growing or maintaining profitability. That value prospect seems ridiculously simple, but it seems to work: Whatever they can provide at a competitive cost, whatever retail segment that is, they’ll pursue it. It’s known as a home improvement chain, but my family gets its laundry detergent and other household things from Menards more than any other store.

HR: What benefits does Menards derive from being headquartered in Wisconsin?

TK: They’ve been here since the beginning of the company, so they do have deep roots here. But generally in Wisconsin, they have access to a well-educated, low-cost workforce to draw from. Housing is very affordable here compared to other locations in the Midwest, which is likely another benefit.

HR: What are some of the biggest challenges Menards has faced in its history?

TK: Over the years, their challenges with various regulatory agencies have probably been difficult. Menards is pretty tight-lipped about their internal practices and lots of other things. As a private company, they don’t have to disclose much and by and large, they don’t.

HR: What opportunities and challenges do you see for Menards in the future?

TK: I think their willingness to offer products that aren’t traditional for a home improvement chain will increasingly serve them well over time.

In terms of challenges, I think their industry is likely to continue to be strong. People talk about “the end of brick-and-mortar retail,” but I don’t think that’s super applicable to them. Certainly online competition will pose a challenge to some degree, but customers just aren’t going to buy

two-by-fours from Amazon.

Market and Opportunities

Hardware Retailing (HR): Can you describe the average Menards consumer?

Anne Brouwer (AB): In general, I would say their customer is probably not too different from those of Home Depot and Lowe’s. Menards’ customers are often looking for a lot of the same products and services. There are a number of markets where these stores overlap, and in those markets, a Menards’ customer might be slightly more price-sensitive.

HR: What is Menards’ position among its major competitors?

AB: When you talk about Menards, they’re clearly No. 3 after Home Depot and Lowe’s. But they’re a regional player and often about one-tenth of the overall size of these major competitors in terms of earnings. There’s a significant difference in the productivity among these three companies. Most of these companies have 200,000-square-foot stores, but Menards brings in $10 to $12 million less per store.

HR: What opportunities can Menards capitalize on in the coming years?

AB: One of their biggest opportunities is to look at how to increase the productivity of each store, rather than building new stores, which is costly.

I think Menards’ opportunities fall into three main areas. One is improving operational excellence, which starts with recruiting and training the right kind of people with the right kind of skills. It includes improving their processes, in-store and beyond, and it includes their ability to solve problems and deliver a satisfactory solution to customers.

Another area is in information and data management. That involves an underlying combination of systems and analytics and access to accurate, timely information.

The third area is culture. Menards has a reputation for not necessarily always being a happy place to work or a satisfying place for customers, particularly post-purchase. These challenges are not unique to Menards; many retailers need continuous improvement in these areas.

HR: Can you discuss Menards’ e-commerce presence compared to Amazon and direct competitors Home Depot and Lowe’s?

AB: I think you could argue that they’re lagging behind in that area. This is clearly one area that represents an opportunity for them. It’s an area that’s tough for all retailers, not just Menards, because so much is changing so quickly, and the consumers are often far out in front of a retailer’s current capabilities. It’s a huge investment of resources. It’s time, money, skills and access to the right solutions.

HR: You’ve called Menards a “regional player.” What benefits come from sticking to certain regions as opposed to expanding?

AB: It takes huge investments to open new stores. Unless you have a model that gives you a break-even and return on investment, new stores can sometimes give you a temporary boost, but not always a sustainable long-term model. In the last few decades, lots of retailers expanded too quickly and now have too many stores, leaving them needing to shrink their retail footprint because they need to invest in other touch points to match customers’ needs.

The second advantage of staying regional should be to more deeply understand their trade area and tailor their products and services to meet that demand. They should, theoretically, be able to outmaneuver national chains that might not be able to understand or capitalize on differences between regions.

If you look at home improvement, we already have two very strong national players and strong independent competitors and local specialists like lumberyards and plumbing, kitchen and lighting product suppliers. You have to ask whether there really is room for a third national player in these markets. There may be opportunities in mid-size markets for companies like Menards, where Home Depot and Lowe’s would never invest.

HR: What value does Menards derive from being a private company?

AB: Menards has a lot more leeway to run with different kinds of margins, operating profits and net profits than a public company that’s constantly being hammered by the markets and challenged by analysts who expect faster growth and higher profits.

Hardware Retailing The Industry's Source for Insights and Information

Hardware Retailing The Industry's Source for Insights and Information